Deloading in Climbing

Have you ever wondered why you are finally able to send your project after a few days of rest, rather than trying day-after-day? This trend does not appear to be only exclusive to climbing but in other aspects of performance as well. Researchers in a 2003 study found that approximately two weeks of rest in weight-lifters actually increased their maximum squat and bench press weight. This seems counterintuitive, is less really more?

Strangely enough, the answer is that our bodies benefit from deloading. Although often overlooked, deloading is an extremely important aspect of any climber’s training program and can have benefits for both performance and injury prevention. This doesn’t mean that climbers shouldn’t train hard but rather that your body will only be able to progress if the training is supplemented by sufficient periods of rest and recovery.

What is Deloading?

Deloading is a term that describes the time that the body adapts and gets stronger from a reduction in training intensity and volume. Although training is good and prepares us to send our climbing projects it also causes fatigue. This fatigue depletes important systems in our body such as the hormonal and nervous systems which may impair our performance over time. A 2016 systematic review by Schoenfeld et al., found that high training frequency combined with high load resulted in decrements to performance.

These results suggest that limiting the number of times a muscle is trained in a given time may help maximize strength and minimize injury. Hortobágyi and colleagues found that resting for roughly 14 days increased growth hormone by 58.3%, testosterone by 19.2% and decreased cortisol, a hormone related to stress, by 21.5%. These values indicate the amount of work the body is undergoing to assist our musculoskeletal systems to prepare and optimize for performance. As climbing requires engagement and stability of large muscle groups such as the core/trunk, hips and shoulders, this phenomenon may explain why we may perform better after a period of rest.

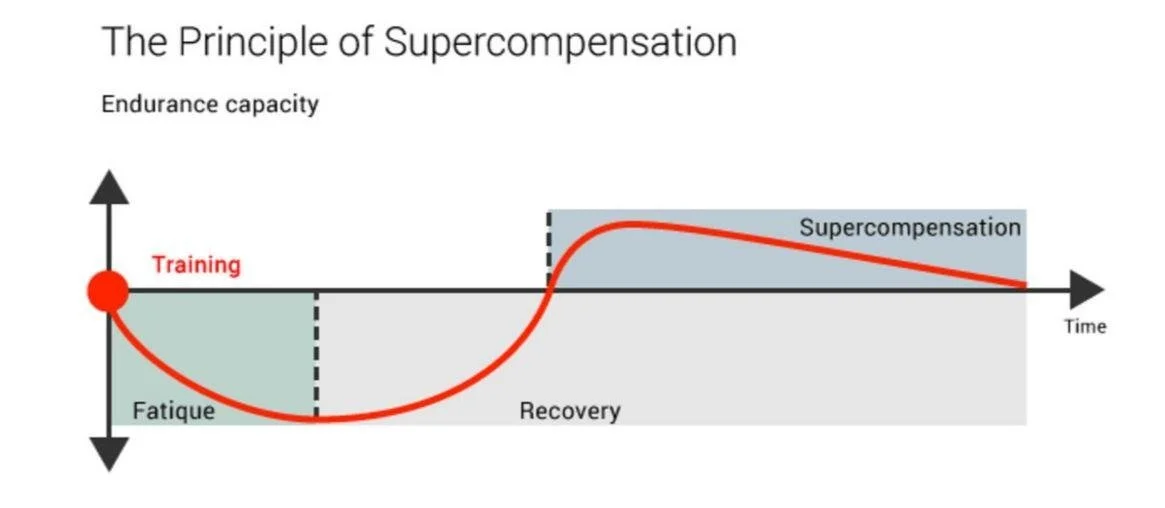

So how can we utilize deloading to optimize our climbing performance? Too short of a deload may not help and too long of a deload might actually lead to our strength and muscle capacity to weaken. For example, imagine you have just begun a new hangboarding program. Initially, your fingers and forearms will feel sore and fatigued, and your climbing performance will likely decrease. A period of rest will enable your body to recover leading to supercompensation and ultimately increased climbing performance and finger strength.Without a rest period, your forearm muscles, finger joints, and tendons will not be able to recover and adapt and an injury (for example a strained or ruptured pulley) becomes more probable. If you’re worried that you might lose your performance gains, a 2012 study found that deloading for 8 weeks did not change overall hand-grip strength.

So, what’s the best way to deload? Unfortunately there is no one “best” method for deloading as it will depend on a variety of factors such as your climbing level, how long you’ve been training, your nutrition status, your sleep, past injuries, and your genetics.

Even other commitments and stressors in your everyday life such as work or family can impact your ability to recover. However, a good place to start would be to consider implementing a deload week every 4-6 weeks. A deload week doesn’t necessarily mean you can’t do any climbing or training at all, but aim to reduce your total training load by at least 50% by reducing frequency, duration, intensity, or a combination.

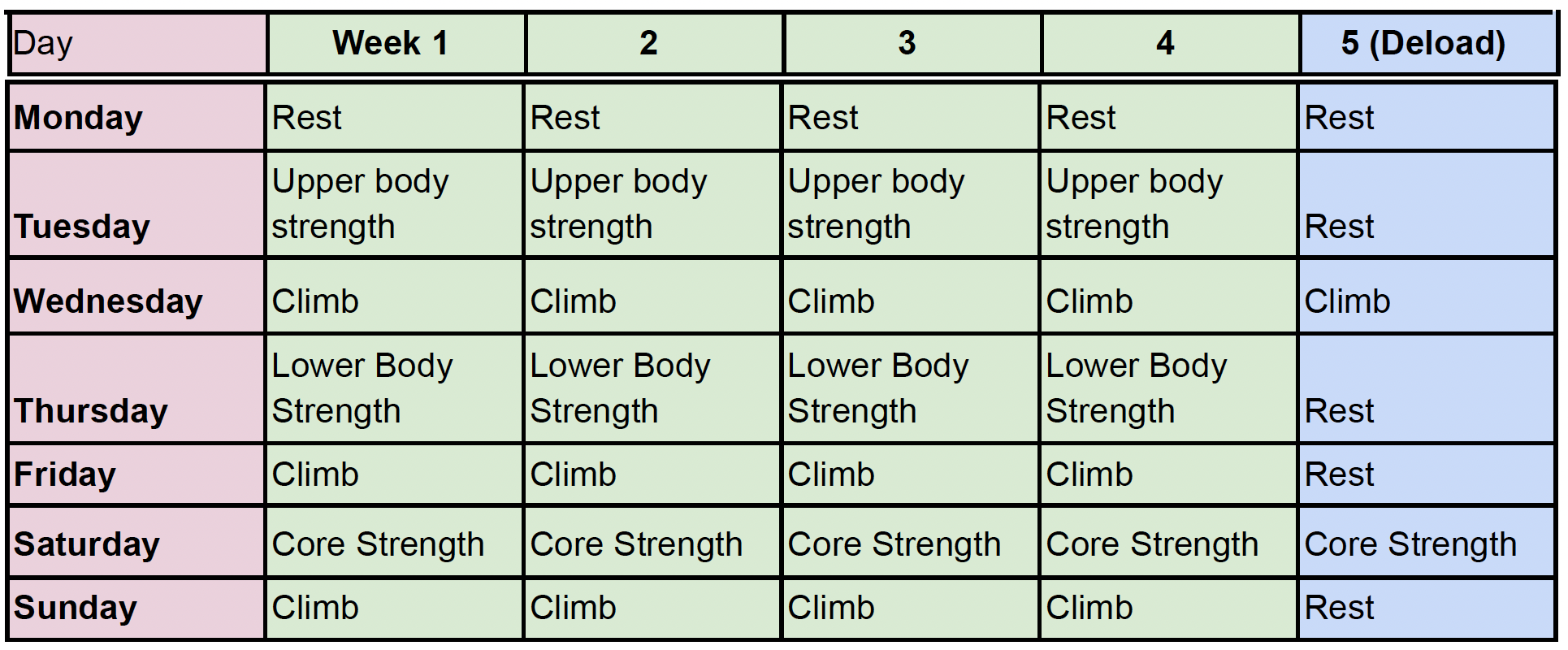

For example, if you normally climb 4 times per week you could climb 4 times per week during your deload week but reduce the length of your session. Alternatively, you could keep the length and difficulty the same, and only climb 1-2 times that week. An example of a 5-week training/deload cycle is displayed below. Keep in mind that this is just one example, every athlete's training program will look different based on the individual differences discussed above.

Finally, one of the best ways to determine when you should implement a deload period into your training and prevent injuries is to recognize the signs of overtraining. Things to lookout for include: decreased performance, chronic fatigue, unintended loss of body weight, becoming ill more frequently, decreased motivation, sleep disturbances, irritability, and inability to concentrate…the list goes on. If there’s anything to remember from this article is that listening to your body and allowing for rest and recovery when it's needed is the best way to promote your performance and longevity in climbing!

Bio

Rachel is a second-year physiotherapy student in McMaster University’s MSc Physiotherapy program. As a former competitive gymnast and current avid rock climber she has a passion for exercise sciences and sports rehabilitation and hopes to have the opportunity to specialize in climbing physiotherapy when she graduates.

Co-Author: Waldo Cheung https://www.linkedin.com/in/rehabinapinch

Works Cited

1. Vann, C. G., Haun, C. T., Osburn, S. C., Romero, M. A., Roberson, P. A., Mumford, P. W., ... & Roberts, M. D. (2021). Molecular differences in skeletal muscle after 1 week of active vs. passive recovery from high-volume resistance training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 35(8), 2102-2113.

2. Ratamess, N. A., Kraemer, W. J., Volek, J. S., Rubin, M. R., Gomez, A. L., French, D. N., ... & Dioguardi, F. (2003). The effects of amino acid supplementation on muscular performance during resistance training overreaching. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 17(2), 250-258.

3. Hortobágyi, T. I. B. O. R., Houmard, J. A., Stevenson, J. R., Fraser, D. D., Johns, R. A., & Israel, R. G. (1993). The effects of detraining on power athletes. Medicine and science in sports.